![What To Do If You Have A High Product Return Rate [6-step Process]](https://www.agiliantech.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/What-To-Do-If-You-Have-A-High-Product-Return-Rate-6-step-Process.jpeg)

What actions should you take if you find that you have a high return rate on your new product that’s hit the market? We’ll discuss the 6 steps to follow in order here…

What’s the product return rate?

A product return is when you have a product that was purchased by end users who, for whatever reason, didn’t have a good experience and decided to return it. For example, they purchased sneakers online and the fit wasn’t right or a tablet they bought wouldn’t power up.

The return rate is the percentage of units sold that were returned for whatever reason out of the entire number sold and is usually considered to be a KPI for many manufacturers.

How to calculate the return rate?

The way you will calculate the return rate is to take the number of units returned and divide it by the total amount sold, then multiply by 100 to get the percentage.

For example, let’s say you sold 15,000 units but 5,000 were returned. That would be a 33% return rate.

The percentage return rate you have will vary depending on your product type and industry. For example, in the retail industry, it’s fairly normal to have around a 16% return rate on the merchandise which is very high from an engineering, electronics, or manufacturing point of view, but not in retail. In fact, Amazon often has up to around a 20% return rate.

Why so high?

Amazon has millions and millions of products on sale. 20% may seem high, but if you consider the numerous reasons why customers return products and that there are millions being sold each day, it’s not that bad of a rate in that kind of mass retail marketplace where the large companies don’t usually develop their own products, but work with other suppliers to buy and sell a multitude of different products (the same can be said for stores like Walmart, too, for example).

Where this wouldn’t be acceptable is electronics and higher-quality items like watches, for instance, which are expected to have a far lower return rate due to their value and customer expectations.

Reasons for returns

- Buyer’s remorse accounts for the majority of returns

- NTF returns (no trouble found) are when a product just isn’t right and is returned with no issues

- DOA products that don’t work from the start

- Poor quality products

- Unreliable products

👉 Read about these 5 reasons and why they cause returns in more detail in this blog post: 5 Main Reasons For A High Product Return Rate

Why test product reliability?

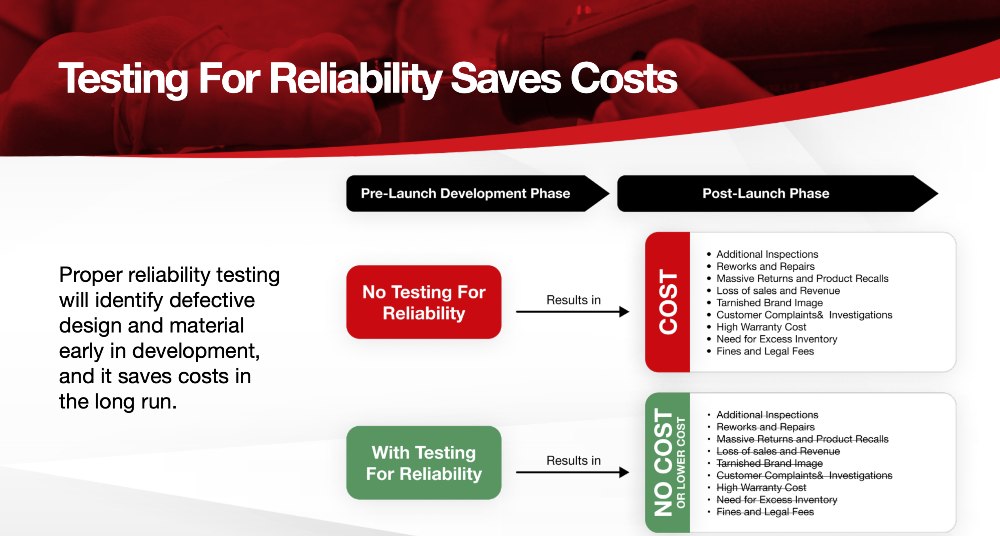

We’ve written before about the many benefits of product reliability testing and it certainly has an effect on your product return rate. Almost every return, even NTF products, is a cost to the business. Consider that the return shipping may need to be paid for, the package is received and handled by an operator, and the product needs to be checked and tested thoroughly before it can be resold, and then repackaged and shipped again.

If this can be avoided, the financial benefits should be clear, and reliability testing to weed out defects in the product design or materials will go a long way to stopping quality and reliability issues that cause many returns:

Quality and reliability are major focuses for us and should be for you, too, if you value a low return rate and customer satisfaction.

What to do if you are experiencing a high return rate?

If you’re suffering from a high return rate and products currently being sold are coming back for the different reasons outlined earlier, it’s time to investigate why and take action to put it right. Here are 6 steps for how you approach and solve the problem:

1. Triage

Triage typically means the categorization of all the returns. In the triage process we follow some steps:

- This is just a visual check on the product that takes note of the way you received it. Was the box torn or intact, was the product itself intact and not broken, are there any missing parts or adapters, etc?

- Perform a functional test. Assuming the product was intact, the box is intact, and everything seems visually fine, you then plug in the product and do a functional test (for electronics). You’re checking whether it’s powering up or not, if the functionality is correct according to its specification, and, if there is an issue, checking what it seems to be. An example would be a battery-powered vacuum cleaner that doesn’t power up. You might notice that an LED is blinking saying that the battery is low, and after plugging it in you see that the battery is not charging. That’s a charging issue, therefore you need to categorize it.

- Categorize the return into the correct bin. In the example of the vacuum cleaner, you could say it’s a design issue and place the item in the ‘design bin’ for R&D to examine, or you may categorize it as a ‘component or supplier issue’ which could also be right if a battery is not working correctly. You need to make the call depending on how you’ve decided to categorize returns during triage. A small deformity on the plastic housing, paint that smears in contact with water, etc, would probably belong to the ‘manufacturing’ category. Finally, if the item passes the visual and functional check, it can be categorized as ‘NTF’ and placed in that bin instead. The correct teams will then examine the returns associated with their departments to find out why the issues occur.

2. Establish a sustainability team

Following triage, we’ve categorized product returns based on the issues they seem to have. To attack these issues we establish a ‘sustainability team’ that includes a member from design, manufacturing, quality, reliability, and any other member with relevant skills or experience for this type of product. There will also be a manager to coordinate their meetings, take notes, and assign actions. There will commonly be one team per type of issue (Design, component & supplier, manufacturing, raw materials, and NTF).

The team then works to troubleshoot the issues found with the aim of fixing them in the product so they don’t occur again in future, hence the different disciplines in the team as the design team might need to adjust the product design based on suggestions from reliability and manufacturing, for example.

3. Cross-functional contribution to sustainable engineering

When the design engineer or design team receives the triaged returned units they need to go through a whole checklist to determine what the root cause of each failure is and also determine whether or not this has been a consistently bad design that is happening from the old version of the product to the new version, or if it’s a new issue that they have never seen in the design.

An example would be where a lot of the devices are coming back broken and the customers are saying that they were rolling off of tables and breaking when they hit a vinyl floor. The engineer will consider if it is acceptable in the industry for a product to break from that height when falling onto a vinyl floor. If it’s a glass material that would easily break at that height then it may be assigned as the fault of the customer, however, if it’s another material that should withstand such a drop, this is a reliability/durability issue that needs to be fixed. If not you can expect customers to okay you don’t have to do anything about it blame it on the customer but if it’s not glass if it’s something that should endure that height and should not break and it’s only going to look bad on your product in terms of durability and reliability you must fix it if you don’t fix it people will stop buying your product and will purchase from your competitors with more durable products.

That’s an example of product reliability, but you may also have an issue raised by the quality engineer who might say that a gap is just not acceptable as it’s too big, looks ugly, and is causing customer returns because they don’t like how it looks. Another would be where poor components are failing and making the reliability life on the product low because your supplier doesn’t check their quality well enough. In this case, you need to work with the supply chain team to go and look for more reliable suppliers. Finally, in manufacturing, you may have issues with LEDs, for example, where poor soldering is causing them to fail, meaning that your manufacturing process wasn’t tested thoroughly enough and needs to be adjusted, or intermittent problems that only occur to customers after you ship the product. In this case, not enough testing was done to find those issues before shipping.

Ultimately they aim to come up with a good solution that fixes the problem once and for all.

4. Update the lessons learned database

The solution put in place will also be documented in a database called the ‘lessons learned database’ for future reference. This means that the process is controlled and documented and if future returns come in, the sustainability team can check the database to see if the issues are related to the previous fix or if they’re something new again.

5. Manufacture a new-build product with the fixes

In the case of the product that breaks when dropped onto a vinyl floor from table height, your reliability engineer will have a discussion with the design team about why based on the industry and what our competitors offer, this fault is not acceptable. So we must make our product more durable. The new design is made, developed, and rolled out to production following the regular NPI process. There is going to be a cost of making the product better, but the cost of the return and of losing customers, as well as damage to the brand, will be much higher if we don’t fix it.

6. Monitor the field return rate of the new-build product

The issues have been fixed, a new version of the product was developed and launched, and now it’s on sale.

The final step is to monitor your field return rate and find out whether or not you’re seeing those same issues again or not. If you are seeing it again there are some serious issues that need to be dealt with, but if you’ve done a good job and the product design was not the main problem then most likely you will not see those issues anymore.

Conclusion

These tips will help you to lower the return rate of an existing product, but they will not necessarily get rid of all returns because your inherent design or testing processes were not sufficient to completely get rid of the issues in the first place.

In order to ensure you have a very low return rate, you must follow a system similar to ours that helps ensure that high-quality and reliable products will leave production and end up in customers’ hands minimizing the likelihood of returns due to quality and reliability, at least.

Watch this video to learn more about how to reduce issues in this video:

****

Are you suffering from a high return rate? What did you do to fix it? Let us know by leaving a comment.

We’re here to help, too, so if you need advice from our product development and manufacturing team about your project, just get in touch by contacting us.

Author

Our head of New Product Development, Andrew Amirnovin, is an electrical and electronics engineer and is an ASQ-Certified Reliability Engineer.

He is our customers’ go-to resource when it comes to building reliability into the products we help develop. Before joining us he honed his craft over the decades at some of the world’s largest electronics companies such as Nokia, AT&T, LG, and GoPro.

At Agilian, he leads the New Product Development team, works closely with customers, and helps structure our processes.

P.S. What about avoiding returns in the first place?

In this post, we’ve focused on returns coming in from a product that has been on sale and how to react to the problem.

It is often better to be proactive than reactive, so how about reducing the chances of returns happening before your product goes on sale?

It is possible to do so, and I shared some tips about that right here: 7 Secrets Behind Low Product Return Rates